A Little Neighborhood History

East 20th Street looking east in the direction of First Avenue, ca.1938. Two of the huge gas holders appear in the foreground.

Peter Cooper Village Stuyvesant Town (PCVST) stretches from First Avenue to Avenue C and from 23rd Street to 14th Street. The 80-acre tract has a rich history. The area was originally called the Gas House District because it was dominated by giant gas storage tanks, or “gashouses,” from the mid-19th century to mid-20th century.

Buildings in the Gas House District, early 1940s

These tanks often leaked and made the area undesirable to live in, even becoming the namesake of the Gas House Gang, a popular New York City gang that operated in the area. As a result, residents of the district were predominantly poor, and many were immigrants from Ireland, Germany, and Eastern European countries. However, the area began to flourish during the 1930s, following the removal of the tanks and the construction of the East River Drive, known today as FDR Drive.

Recognizing opportunity, the district became part of the large-scale urban renewal projects championed by Robert Moses in the 1940s. Moses sought to clear the area and build a housing development in anticipation of the returning World War II veterans and in lieu of a housing crisis which originated during the Great Depression. He convinced MetLife Insurance Company to build the complex, based on an earlier development in Parkchester in The Bronx. As a result, 600 buildings, containing 3,100 families, 500 stores and small factories, three churches, three schools, and two theaters, were razed. As would be repeated in later urban renewal projects, some 11,000 people were forced to move from the neighborhood through eminent domain.

Construction of Peter Cooper Village Stuyvesant Town, ca. 1945

Construction of PCVST took place between 1945 and 1947; 110 buildings and 11,250 apartments were erected. The complex received 7,000 applications within the first day of initially offering the apartments and veterans received selection priority. Rents ranged from $51 to $90 per month. The complex’s first tenants, two World War II veterans and their families, moved into the first completed building on August 1, 1947. By that time, the complex had received 100,000 applications.

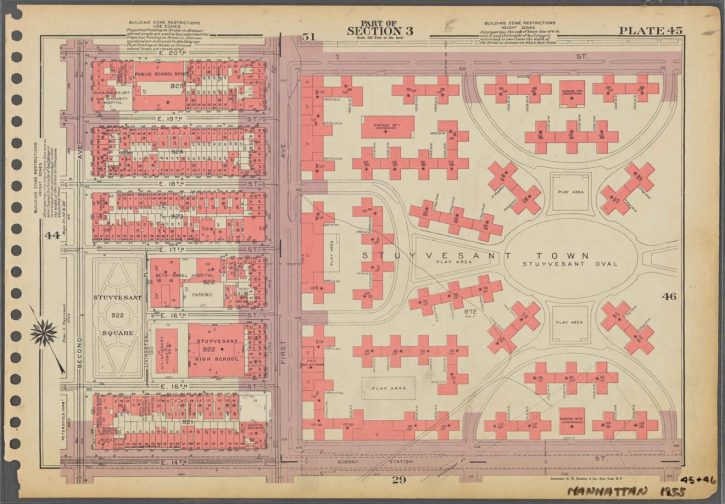

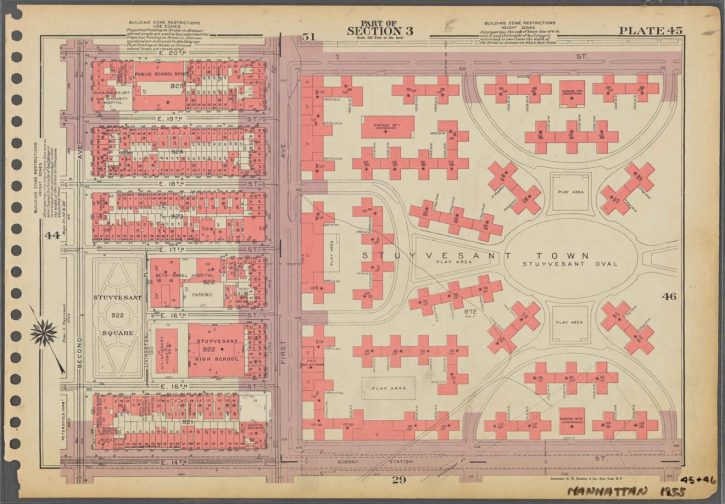

Historic building zoning map of PCVST and the surrounding area, ca.1955

MetLife President Frederick H. Ecker said that PCVST would make it possible for generations of New Yorkers “to live in a park – to live in the country in the heart of New York.” However, this did not extend to all New Yorkers. The only veterans MetLife Insurance Company supported were white veterans. The company, Moses, and prominent politicians discriminated against Black people and barred them from living in PCVST. They believed allowing Black people to live there would harm the complex’s profitability and make the area less desirable. Lee Lorch, a City College of New York professor, petitioned to allow Black people into the development, and was fired from his teaching position as a result of pressure from MetLife. Upon accepting a position at Pennsylvania State University, Lorch allowed a Black family to occupy his apartment, thus circumventing the rule. However, as a result of pressure from MetLife, he was dismissed from his new position as well. He ultimately had to leave the country to get work, in Canada, and remained in exile there for six decades. He died in Toronto in 2014.

Lawsuits to combat this sanctified segregation abounded. White residents of PCVST teamed up with Black activists to form the Tenants’ Committee to End Discrimination in Stuyvesant Town. Many of the veterans saw these racist policies as an extension of fascism, which they had fought against during the war. After nine years of activism, MetLife allowed three Black families to move into PCVST. The three white families who volunteered to leave had to promise to never return. Ultimately, this fight for equality helped lay the groundwork for the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which made housing discrimination a federal crime.

PCVST once contained original plaques honoring Frederick H. Ecker and marking the complexes as housing for moderate-income families, which were dedicated during the complex’s opening day in 1947. In 2002, when the property went luxury market rate, the plaques were removed.

In October 2006, MetLife sold PCVST to Tishman Speyer. The new ownership implemented significant capital projects on the property. Tishman Speyer relinquished control of the property in 2010. CW Capital remained the owner from 2010 until 2015, when they sold the property.

Today, the property is controlled by Blackstone/Ivanhoe Cambridge and is home to over 30,000 residents. Rents range from approximately $1,500 per month for a two-bedroom apartment to roughly $13,000 per month for a five-bedroom apartment. Some units are part of affordable housing and are rent stabilized. They remain immensely popular, 75 years after the units were first built. Much like in the 1940s, PCVST is a coveted home for people of all ages.

Peter Cooper Village Stuyvesant Town Today